Every work of art is an uncommitted crime.

—Theodor W. Adorno, 1949.

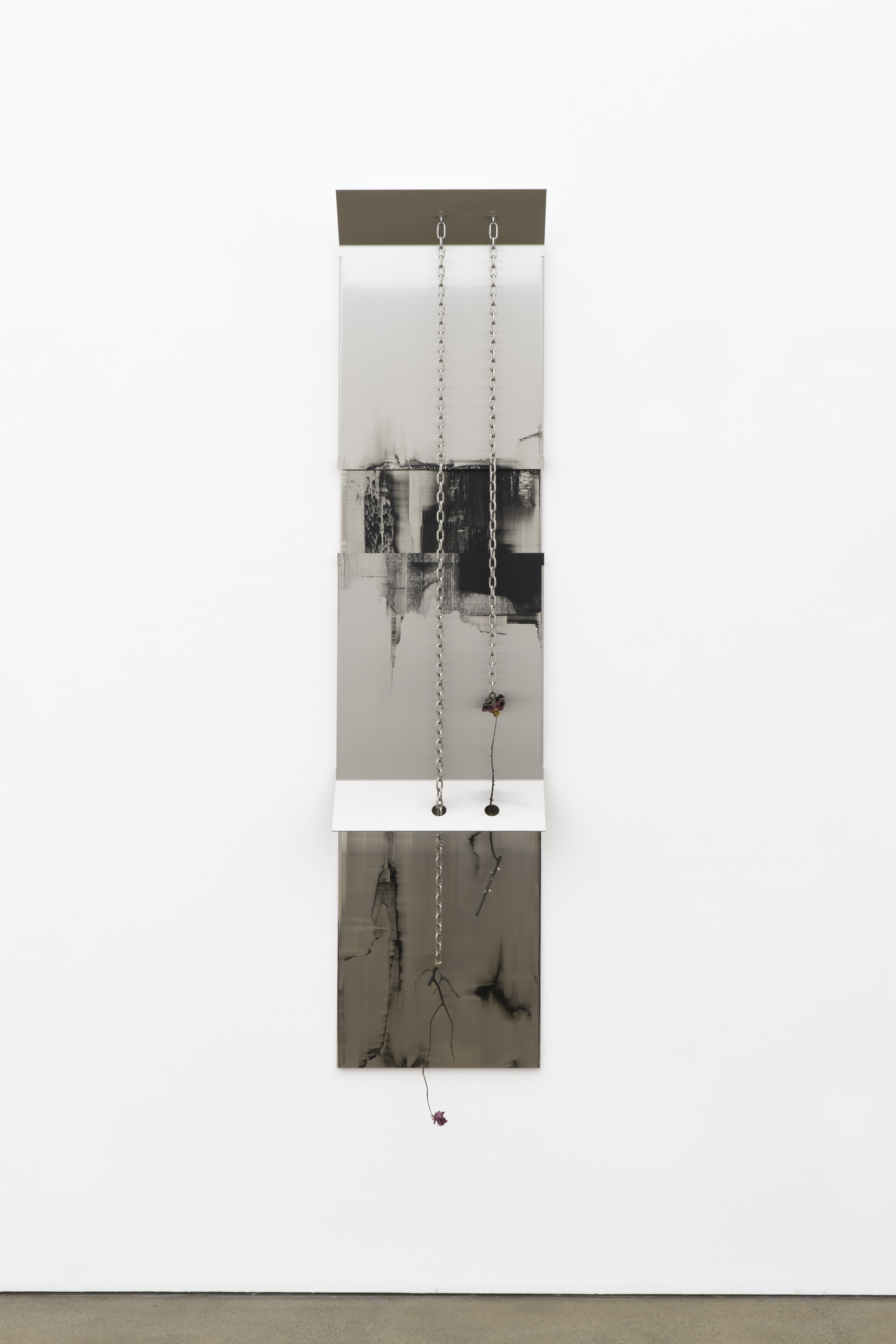

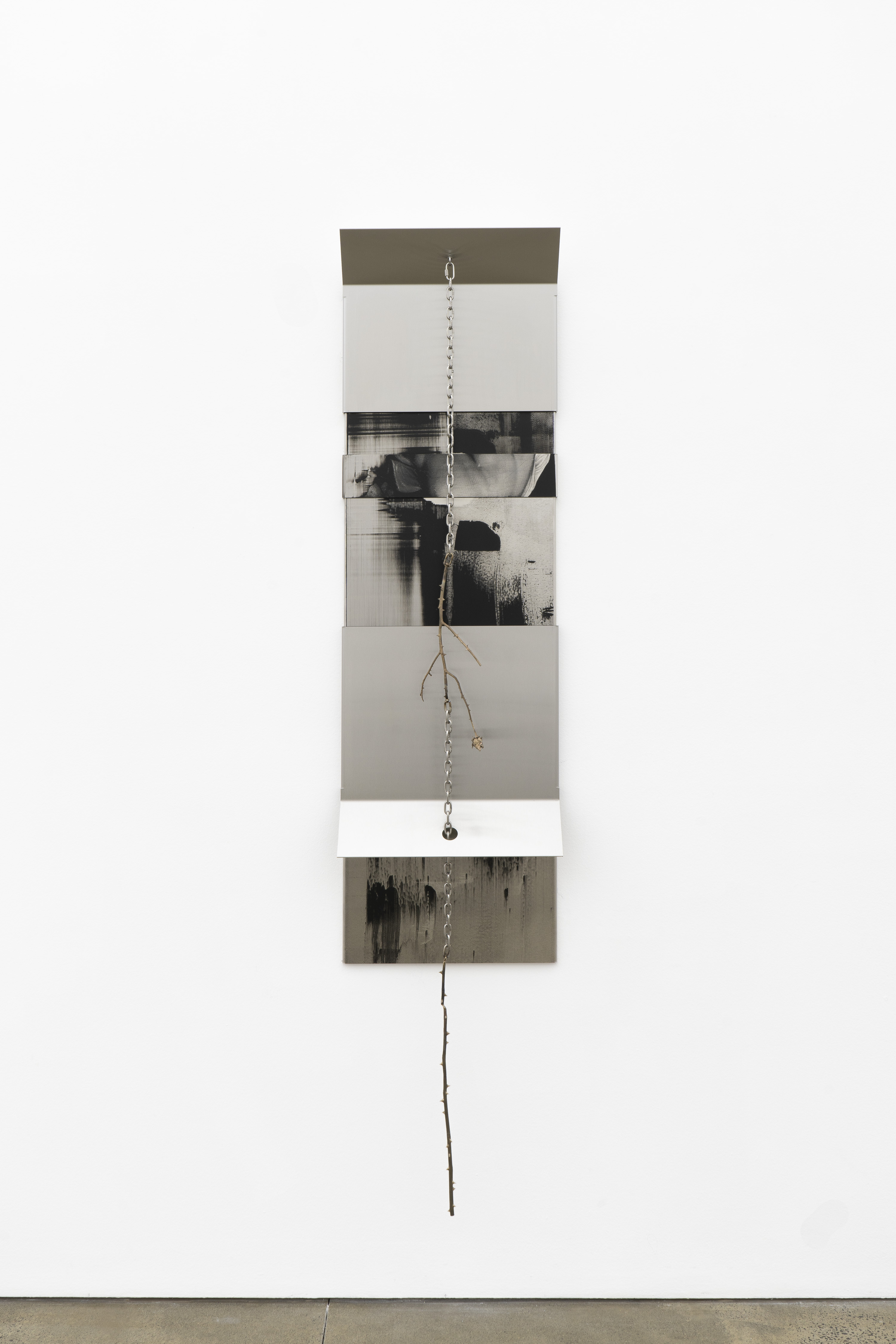

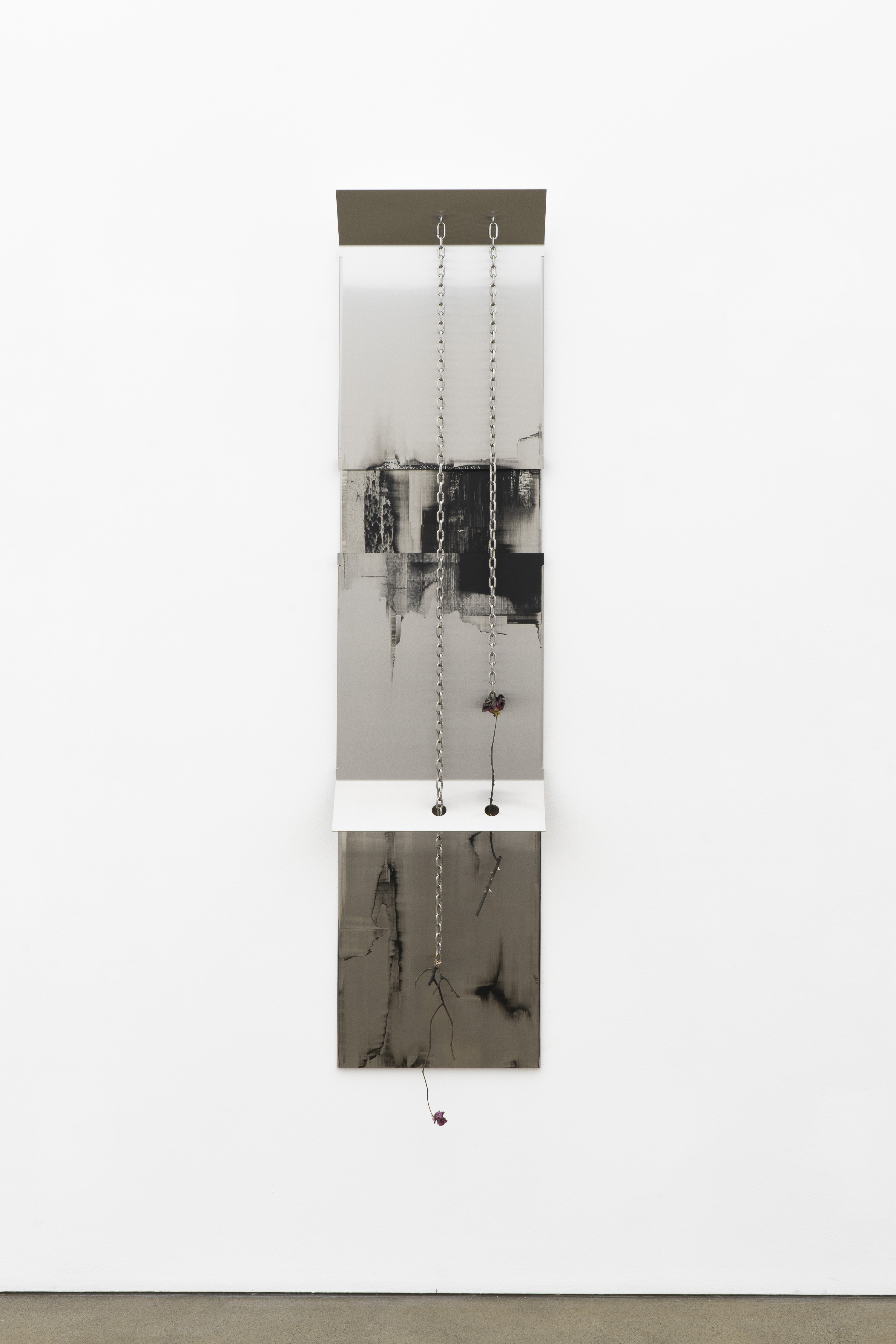

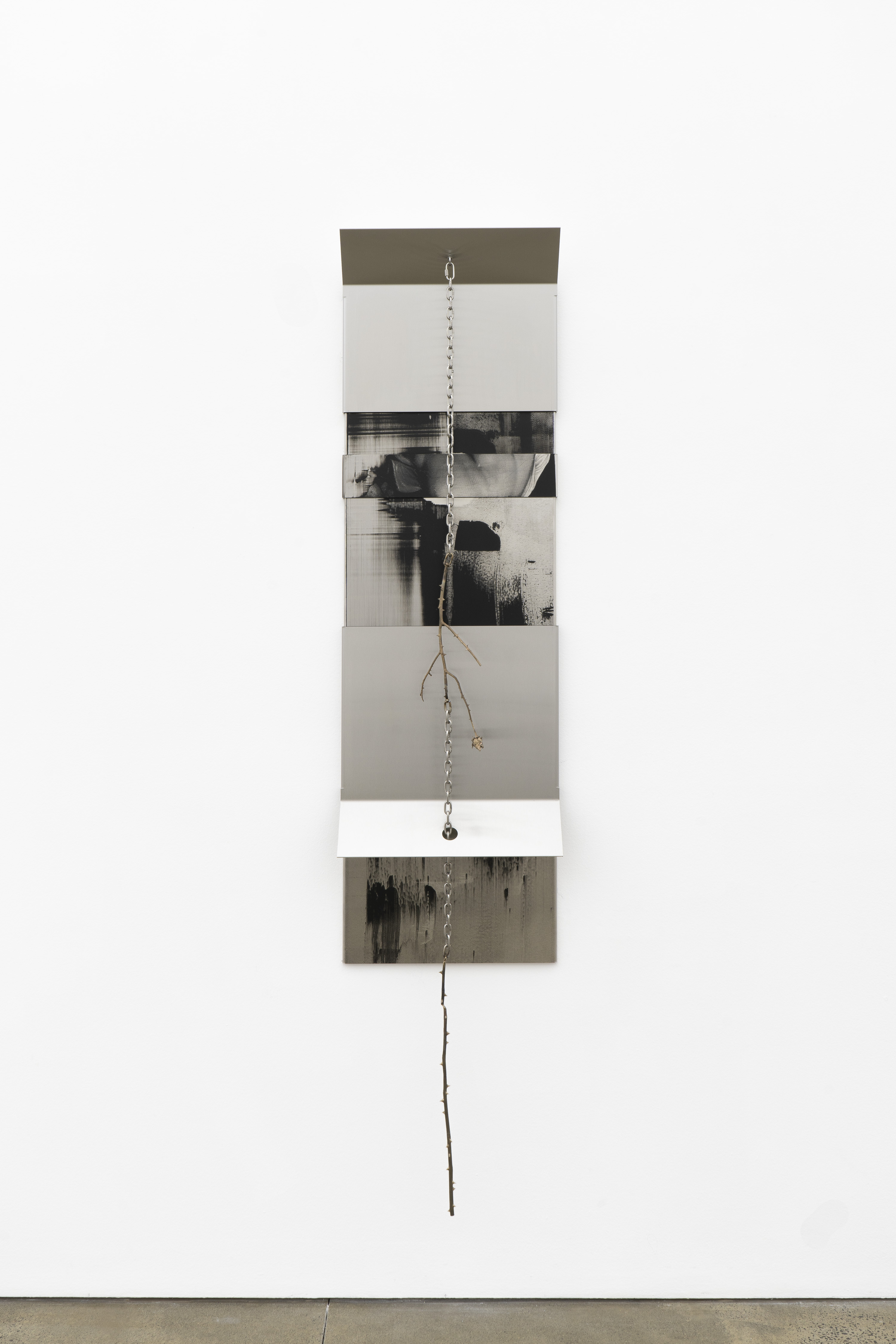

Rob McLeish’s SNARES is a compelling continuation of the artist’s ongoing exploration of visual history, entropy, iconography and base urges. The new series features ten stainless steel panels sparingly festooned with vertically suspended chains chaotically welded to heavy, detailed casts of wilting roses. In a gesture of austere industrial origami, each gleaming panel is layered with overlapping, cleanly folded planes, their outer sheet perforated with a hole (or holes) through which the chains neatly pass, perfectly centred. Providing a rustic tether between wall-mounted art and its mimetic space, and the real space of the gallery, a few extend to coil on the ground below.

Like the post-war minimalists, McLeish is clearly captivated by the seductive quality of industrial materials. This reverence is manifest in the unyielding preservation of flat surfaces and precise, laser-cut forms which bear no visible fixtures or connection points. This almost autistic attraction to the aggressively inorganic geometry of the factory produced reveals a heightened libidinal dimension. Indeed, the amalgam of steel, chains, bronze casts of wilting, abundantly thorned roses (an obvious allusion to waning desire and death) inevitably reminds one of bondage and restraint.